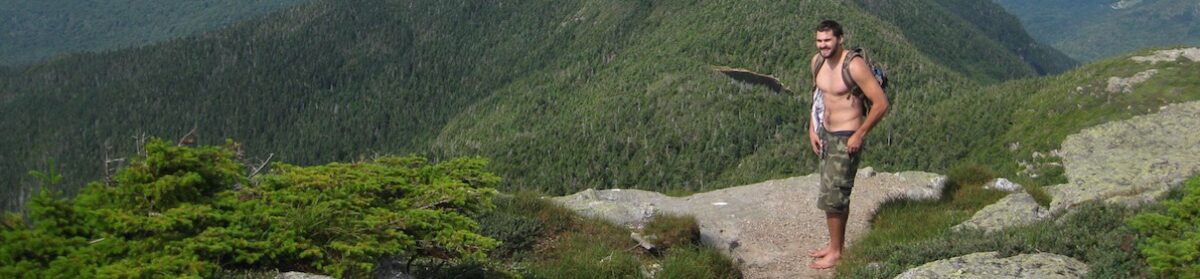

Sitting here in the millenial shadow of Mt Abraham, aglow with the setting sun, my thoughts turn to endings, and by extension, beginnings. She presents a stoic countenance, completely unmoved by the extremes of Vermont weather, or by the changes tiny humans have wrought to her kingdom. I have spent countless hours trekking on her winding trails, through radiant birch stands, past giant moss-covered boulders, into fragrant pine dells. The mountain is a meditation. In my twenties I often climbed alone, drinking in the secrets and deep mysteries as I unraveled my own. The mountain is a confidante. At three years old, my firstborn Sylvan joined my father and me, scampering and exploring and delighting in every bend of the trail. The mountain is a teacher, an outdoor classroom, a living book. Two decades later, Lucas joined me on my Appalachian / Long Trail hike, culminating on Mt Mansfield. A dream fulfilled. The mountain rewards effort with euphoria.

My sons knew my end-of-life directives. “Scatter my ashes from the top of Mt Abraham”. They knew my favorite spots. I never doubted that both of my boys would outlive me, and carry out my wishes. Yet…it was I who carried the ashes of my son with me, close to my heart, on my late winter hike. Two years after Luke’s death, I felt some closure, an ending.

The other day I listened to a podcast by Griefwalker, whose simple wisdom struck me. “Transforming the language of death”. He spoke of our death-phobic society, and of the need to embrace real, direct talk as a first step, eliminating the euphemisms that are so often used in polite (avoidant) conversation. “She passed.” Or “He left us.” These terms, while softer and perhaps more digestible, do a disservice; they baby-foot around the reality and deny us the occasion to acknowledge this unescapable life event. I remember getting a phone call about a loved one who died suddenly and unexpectedly. “She’s gone”. My bewildered response was “Where did she go?” Thinking, we need to find her. It took several awkward back-and-forths of this nature until I grasped that she had died.

As a grieving Vilomah one of the greatest challenges has been to accept that my child is dead. I know I speak for all bereaved parents when I say we wish we could change this horrible new reality. I yearn to return to my mundane before-the-accident life, to hear my son’s voice, to hug his solid frame. Learning to accept the bitter emptiness is difficult because WE THINK WE ARE IN CONTROL of our lives. Yet as Griefwalker states, we do NOT “get to vote on every important event in our lives.”